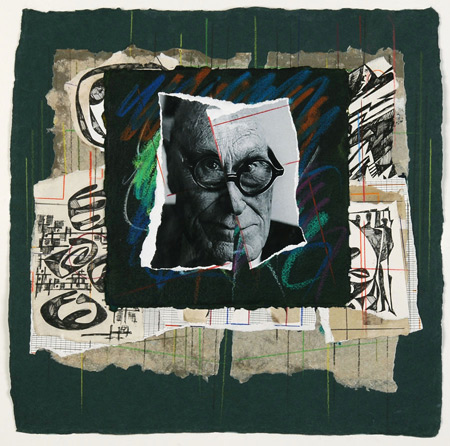

Philip Johnson, 1906-2005, is generally regarded as one of the country’s greatest architects, a man whose 1932 show on the International Style at the Museum of Modern Art (MOMA) introduced the American public to modern architecture and whose designs symbolized the development of a uniquely American form of that modernism. Yet, Johnson is also celebrated for abandoning classical modernism two decades later in order to experiment with a number of different styles that held more closely to the changing tastes of the time.

His is a biography of the highest rank, a “towering figure” who reigned supreme in the history of twentieth century American culture. He was awarded an American Institute of Architects Gold Medal and the first Pritzker Architecture Prize, one of the most prestigious awards in the architectural community. Yet his extraordinary resume did not tell the full story of Philip Johnson’s life and career.

For nearly a decade, in the 1930s and into the 1940s, Philip Johnson did not focus on architectural form or design. Instead, he worked on the form and design of an American fascist society based upon the model of Nazi Germany. In 1932, the same year as his historic MOMA show, he visited Germany and observed Adolf Hitler at a Nazi rally near the city of Potsdam. Philip Johnson fell in love with National Socialism.

Two years later, he resigned his position with MOMA and set out with a colleague, Allan Blackburn, to strengthen an America already infected with the disease of anti-Semitism. Johnson and Blackburn sought to create their own version of the Nazi Party, which they called the “Nationalist Party” and the “Gray Shirts,” modeled on the Nazi Storm Trooper Brown Shirts. When the party failed to attract enough members, both men travelled to Louisiana to offer their services to Huey Long, the controversial populist governor of Louisiana. Distrustful of two Harvard graduates from New York, Long refused their support.

Johnson and Blackburn found their spiritual home in Michigan, and joined Father Charles Coughlin in his campaigns against the administration of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt and the negative influence of Jews in American life. Johnson and Blackburn supervised the printing of Social Justice, Coughlin’s anti-Semitic magazine, and organized a massive rally for Coughlin in Chicago, where more than eighty thousand spectators heard the “radio priest’s” anti-Communist and anti-Semitic rantings. Coughlin stood on a podium designed by Johnson that was modeled on the one used by Adolf Hitler at the 1932 Potsdam rally.

In 1938, Johnson was invited by the German government to attend a summer program in Berlin to learn the basics of Nazism and to hear Hitler speak at the greatest of the Nuremburg rallies, immortalized in the film” Triumph of the Will,” by the director Leni Riefenstahl.

In his capacity as a German correspondent for Social Justice, Johnson toured Poland just a month before the outbreak of war in September 1939. He wrote about his experience that

When I first drove into Poland… I thought I must be in the region of some awful plague…. In the towns there were no shops, no automobiles, no pavements, and again no trees. There were not even any Poles to be seen in the street, only Jews!

At first, I didn’t seem to know who they were except they looked so totally disconcerting, so totally foreign. They were a different breed of humanity, flitting about like locusts. Soon I realized they were Jews, with their long black coats, everyone in black, and their yarmulkes.

A month later, at the invitation of the German Propaganda ministry, Johnson was invited to accompany German troops as they invaded Poland. He wrote to an American friend who had accompanied him to Poland a month earlier about the experience:

I was lucky enough to get to be invited as a correspondent so that I could go to the front… and so it was that I came again to the country we had motored through, the towns north of Warsaw…. The German green uniforms made the place look gay and happy. There were not many Jews to be seen. We saw Warsaw burn and Modin being bombed. It was a stirring spectacle.

By early 1940 Johnson had become directly associated with the American Fascist movement. He was investigated by several government agencies and suspected of being a Nazi spy. Under great pressure, Johnson left his political and journalistic career and enrolled as a Harvard graduate student in architecture. It was the beginning of his efforts to rehabilitate and refashion his public image.

Clearly it worked and for the rest of his career he was Philip Johnson the famous and avant garde American architect. But there were moments of reflection and regret. In the early 1990s, he told an interviewer, when discussing his involvement with Father Coughlin and his time in Nazi Germany, that “I have no excuse [for] such utter, unbelievable stupidity…. I don’t know how you expiate guilt.” One of the ways in which he sought such expiation was in designing Congregation Kneses Tifereth Israel Synagogue in Port Chester, New York. Johnson took no fee for the project because he was so grateful for the support shown him by the congregants of the synagogue.

Perhaps in designing this symbol of Judaism, Philip Johnson found a moment of internal peace. But it did not clear his record or the fact that his activities contributed to American Jewry’s decade of anti-Semitic terror.